This new London map reveals the best ways to walk the city

By charting the city’s most walkable corridors, the Footways project invites visitors to get around by foot.

What a difference a few paces can make. One moment we are shouting over the roar of four lanes of traffic and dodging other pedestrians outside Mile End tube station.

The next we are on a quiet neighborhood street, gazing at rows of large, established trees against a bright blue autumn sky.

I’m on a walk of discovery with Emma Griffin, one of the founders of Footways, a project that traces hundreds of kilometers of walking routes between popular places of interest across London, from hidden gems to well-known museums, luxury hotels and more.

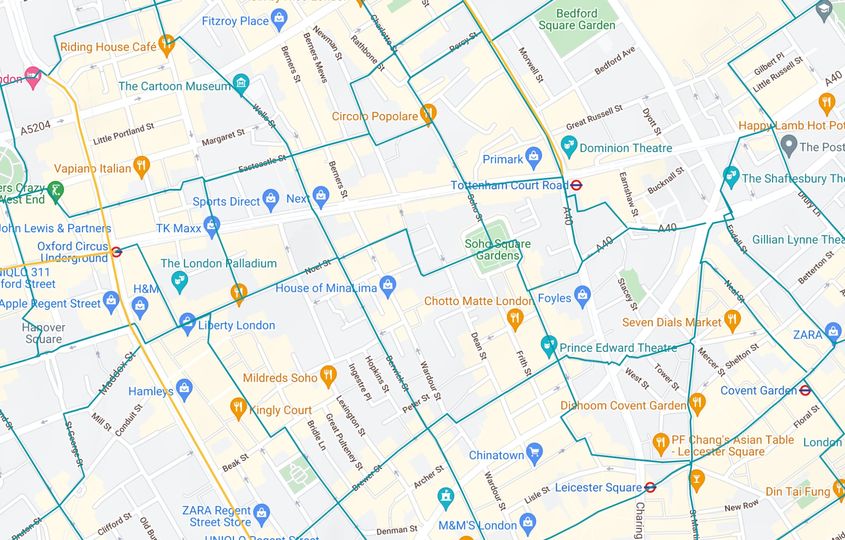

Like a Waze for walkers, Footways directs users to the most pedestrian-friendly paths in the city.

The online version, currently on Google Maps, has been viewed nearly 800,000 times and is gradually being updated and expanded, with a second edition launched in May 2022.

An updated map has been redesigned to make it more legible and includes new routes, taking into account new pedestrian-friendly streets created since the former version as well as Elizabeth line stations.

Footways was launched in 2020 with the aim of getting more people to walk, suggesting new enjoyable routes for walkers and campaigning for improvements in the capital’s streets.

David Harrison, co-founder of Footways, said: “Our aim is to provide attractive A to B routes between key destinations.”

“We have looked for relatively attractive direct routes along enjoyable, quiet streets which avoid polluted main roads, which Google Maps tend to send you along.”

“To a large extent our routes go along really wonderful streets, but at times we have to go for the least bad option, and we will campaign for improvements.”

Walk this way...

Griffin, a street safety activist, started the Footways project through her involvement in Living Streets, a U.K. pedestrian advocacy group.

With funding from Transport for London and support from London borough officials, she and a group of fellow activists and researchers began surveying central London on foot in 2018, mapping out what they saw as the best pedestrian routes between common destinations.

Their criteria: streets that are safe, enjoyable and low on vehicle traffic and pollution.

Filled with tidbits about urban history and destinations such as museums, eateries and public squares, the Footways map aims to show where and how walking can be a better choice than other modes – something that isn’t accomplished by regular street atlases or routing apps.

Griffin’s goal is to re-popularize the most ancient form of urban transportation, as well to build the ranks of a somewhat subversive cause. If more people learn to love getting out on foot, they might fight to elevate the humble pedestrian within a largely car-centric hierarchy of road users.

“We want to present a different vision of the transport network with the pedestrian network as the priority,” Griffin said.

The effort is timely: Walking is one of the most common and easiest activities to incorporate into daily life, but in many places it is in decline.

Stephen Edwards, interim CEO of Living Streets, says the reasons are complex, involving both behavior and the built environment and varying by age.

“We've done targeted research looking at barriers to walking for different parts of the population. For children and parents, there are factors around perceptions of safety and air pollution as well,” said Edwards. “For older people, we see issues around the quality of pavement infrastructure.”

Why Londoners stopped strolling

London has also become more hostile to pedestrians in places. Ride-hailing services such as Uber have lured a number of riders away from public transport, while navigational apps such as Waze have increased motor traffic on some residential roads, creating a less-friendly walking environment.

Apart from pandemic-related standstills in 2020, vehicle miles traveled have steadily increased in London since 2011, despite congestion fees and other attempts to unsnarl the roads.

Yet London’s horrendous driving delays can make walking not only a healthy choice but an efficient one as well. The Footways map highlights how, in central London, walking trips can be just a couple of minutes slower than taxi or public transit.

Compared to the main roads that Google Maps or other navigation apps usually suggest, many pleasant walking routes are just fractionally slower or about the same. And many of London’s side streets are still light on through-traffic.

“The algorithm just misses all the human factors that make walking enjoyable,” Griffin said. “Our thinking was that walking is the best form of transport for enjoying one’s environment. So why not make the most of it and pick out the routes that are the most interesting?”

Finding a new way with Footways

As if to illustrate the point, we stop in our tracks in front of a pretty church, brightly lit in the afternoon sun. It’s a few paces then to Tredegar Square, with a large colonnaded building at the north side and fine Georgian houses on the other three.

We’re in the Tower Hamlets borough, following a fledgling route from Mile End tube station to Victoria Park created by a local volunteer.

So far, Footways’ footprint is limited to central London, Islington and Hackney, but it’s being expanded to the area we’re exploring and other parts of the city.

In a way, Footways echoes London’s famous “A-Z” street atlas. Created in the 1930s by Phyllis Pearsall, who walked around London cataloguing house numbers, junctions and streets, it is now known as the bible for cab drivers (who are also some of the loudest proponents for pro-car policies, including in this neighborhood).

Through their revival of Pearsall’s method, Griffin and her colleagues hope that the more people get out on foot, the greater the constituency there will be for better paths.

The project isn’t the only attempt to improve the urban walking experience by highlighting the best places to do it.

Go Jauntly, a walking navigation app founded in 2016, sits on Footways’ advisory group. Go Jauntly allows users to compare and choose the greenest and least polluted routes or the most direct routes.

Co-founder Hana Sutch sees the app as a tool to boost mental health by helping people get their daily dose of nature within cities.

Research has shown that walking benefits both physical and mental health, reduces sick days from work, and even boosts creativity. It’s also good for local businesses – pedestrians spend up to 40% more than people who drive to commercial corridors.

Mixed-use neighborhoods with housing, shops and places of work and education in close proximity, as well as good public transport links, all encourage people to walk more.

Yet the reality of city streets suggests those on foot are rarely prioritized in infrastructure: On today’s walk, cracked and narrow sidewalks often flank a wide, freshly surfaced roadway. Ambitions for walking often reflect the same picture.

A boost for walking and cycling

Of three targets set as part of England’s Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy in 2015, the only goal almost guaranteed to be met – mainly because it’s so low – is that people will walk 300 times each per year, Edwards said.

A transport strategy in London is trying to move pedestrians up the pecking order, with a walking action plan highlighting low-traffic neighborhoods and ways to measure transportation outcomes that focus on human safety rather than the number of car trips.

Edwards says systemic issues need urgent attention. He wants to see governments meet stronger standards for the pedestrian realm, including higher pavement quality, safer street crossings, and better links to popular destinations.

“If you think of walking down a cracked pavement with a parked car on it, with vehicles speeding down the middle of the road, it can be quite a frightening experience, especially for parents with young children, or older or disabled people,” says Edwards.

“What for some of us would be inconvenient and unpleasant can be a real barrier for the more vulnerable members of our society.”

Footways works with accessibility advocates to identify problems like poor sidewalks, steps and steep slopes, which can stop wheelchair users in their tracks, or risk tipping them over.

Some of these barriers are already represented by icons on the paper and digital maps, and in the future, Griffin hopes to incorporate more detailed information.

She dismisses concerns that making all sidewalks safe and accessible is too big a task, not least while big budgets are still made available for road building.

“The thing we don’t want to do is say, ‘These streets are nice and the other ones aren’t’,” she said. “Every single street in London needs to be good for walking.”

This article is published under license from Bloomberg Media: the original article can be viewed here