Supersonic dreams: how Qantas almost flew the Concorde

Some 60 years ago, the Flying Kangaroo was eager to get hopping faster than the speed of sound.

The year was 1960. The now-iconic Boeing 747 jumbo jet wasn't even a dream on a drawing board, and in fact, Qantas had only just begun flying the much smaller Boeing 707 the year prior.

But the airline’s sights were already set on a distant, dazzling future. The supersonic era beckoned, and Qantas was eager to be in the vanguard.

So eager, in fact, that its then-General Manager, Sir Cedric Turner, published an ambitious op-ed in The Sydney Morning Herald boldly titled “Qantas will buy supersonics”.

Among the article’s claims, Turner says that “windows won’t be necessary” on these aircraft – they'd so high and so fast that there wouldn’t be much to look at. However, to avoid passengers feeling boxed-in, Turner proposed that Qantas would install “TV screens in the ceiling, and perhaps, the walls, showing the scene outside.”

Even on the longest routes, “by the time the passenger boards the aircraft, settles back, has a meal, a rest, and a cup of coffee … it will be time to land,” Turner envisioned: initially expecting flights from Sydney to London to clock in at just 10 hours, plus fuel stops.

A quick trans-Tasman hop across the pond from Melbourne to Auckland would take just 45 minutes in the air, or a little over an hour from gate to gate.

Later plans suggested that Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane to Singapore could be tackled in three hours: given the difference in timezones, you’d take breakfast in the Qantas lounge and reach Singapore in time for a satay and Tiger beer luncheon at Boat Quay.

Here’s how Qantas came so close to flying supersonic, only to change its trajectory along the way.

The supersonic race

Think supersonic and you think 'Concorde'. Of course you do. There's undeniable romance wrapped in the sound of just two syllables, and in the iconic shapes of that needle-nose silhouette and those graceful, swept-back delta wings.

But Concorde wasn't the only supersonic passenger jet clamouring for airlines' attention.

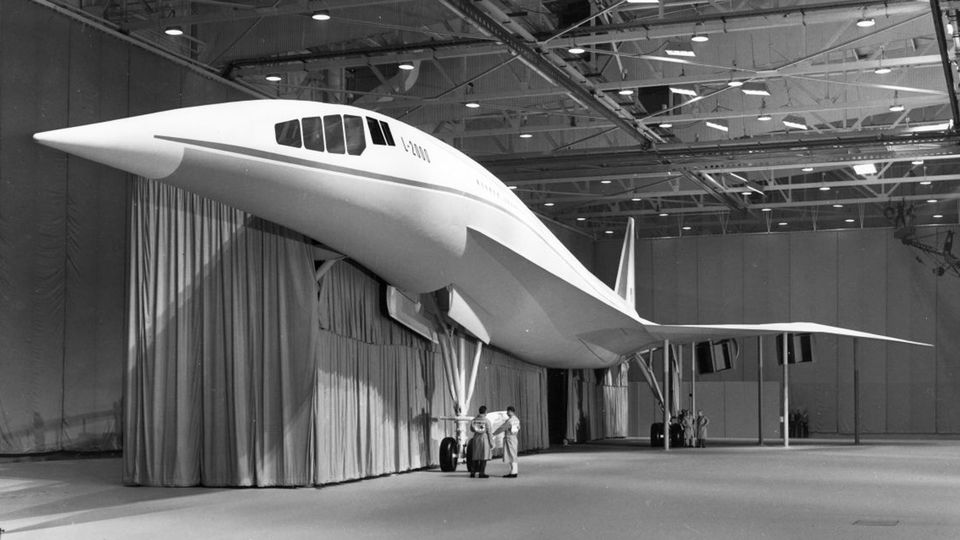

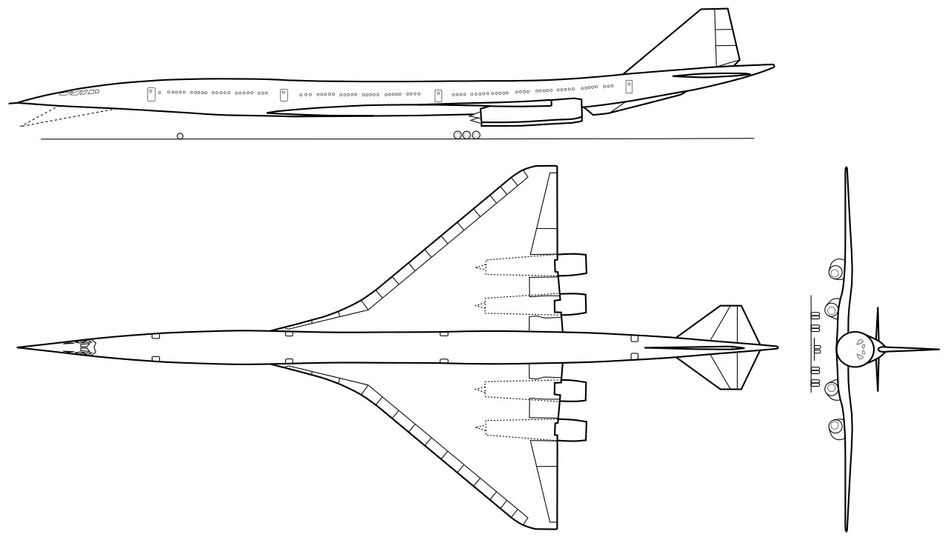

As the faster-than-sound era began to take shape, the Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde was shadowed by the Boeing 2707 (also known as the Boeing SST, for 'supersonic transport') and the Lockheed L-2000.

The Boeing 2707 – its model number chosen in a nod to the Boeing 707, which ushered in the ‘jet age’ of commercial flight – was a wild child of the 1960s, born from the same competitive drive which fuelled the ‘space race’ and with the Presidential imprimatur of Kennedy and Nixon.

The Lockheed L-2000 channelled the same space-age ambitions: in 1960, Hall Hibbard, Senior Vice President of Lockheed Aircraft, said that within 10 years, “Qantas would be using supersonic aircraft capable of (flying) 2,200mph on all flights over 1,500 miles.”

However, Hibbard also expected flying family cars to become the norm by 1970, so there was clearly more optimism than realism here.

Qantas orders ten supersonic jets

When Qantas dipped its toes into supersonic waters in January of 1964, it decided to place deposits on four Concordes and six Boeing 2707s.

These weren’t firm orders – rather, ‘options’ that secured future delivery dates, and allowed the airline to have a foot in both camps, as it wasn’t known which supersonic aircraft would be the more successful, and the safest.

Wikimedia Commons user 'Nubifer'

But less than six months later, Qantas co-founder Sir Hudson Fysh put a dampener on Lockheed Aircraft’s belief that the airline would soon be soaring supersonic, saying that a firm order for any supersonic jet wouldn’t happen for at least another 10 years.

“There is a long way to go before any of the supersonic projects have proved themselves,” Fysh said at the time.

Explaining the airline’s consideration process, Fysh added that “the Concorde will be smaller and cheaper than the others but will be slower and have a smaller payload. The Lockheed looks a very promising proposition. Then the Boeing people are going for a very different project.”

Concorde gets the edge

As the race to get the first supersonic passenger plane built continued to unfold, by March 1966, it was clear that Boeing’s supersonic bird would be years behind the Concorde, and may not be worth the wait.

Aviation analysts at the time observed that the Boeing 2707 would be more expensive than the Concorde for airlines to buy, and to operate: and in return for that added expense, would only shave 30 minutes off a 3,500-mile flight like Sydney to Jakarta, putting pressure on the economics of Boeing-backed supersonic flying.

The Boeing 2707 was also in competition with the Lockheed L-2000 for US Government funding to continue its development: a battle Boeing won on December 31 1966, but was still far away from being ready for an airline to operate.

The Boeing 747 noses out in front

The year 1966 also saw a different type of aircraft appear on the horizon: the Boeing 747.

Rather than flying faster, the jet would travel at regular subsonic speeds, but carry far more passengers on each flight – an idea Qantas quickly subscribed to, ordering four jumbos in early 1967, to join its fleet from 1971.

Although its options remained on both the Boeing SST and the Concorde, this fresh Boeing 747 order presented the airline with a new conundrum.

Would the 747 merely fill the gap in between the Boeing 707 and the winning supersonic plane – continuing with Hibbard’s earlier vision of supersonic as the future of Qantas – or would it take the airline in a new direction, where ultra-fast flying is no longer a priority?

At first, the Boeing 747 was seen as a complement to supersonic flying: allowing Qantas to carry economy class passengers longer distances at affordable prices, and as a better fit for the movement of freight, which would be largely uneconomical to carry in bulk aboard fuel-guzzling supersonic jets.

Even Boeing considered the 747 as merely a short-term solution: a supersized passenger jet which, when eventually replaced by airlines adopting the 2707, would be easily converted into a 'supercargo' jet packed with freight containers from tip to tail.

So in 1970, a year before the jumbo first entered into service with Qantas, the airline’s fleet plans still showed a place for supersonic jets. But in the same year, it became doubtful that the supersonic Boeing 2707 would ever fly.

Boeing bows out of the supersonic race

With the development of Boeing’s supersonic aircraft largely funded by a US Government grant – the one it won over Lockheed in ’66 – by 1970, it was clear that an additional US$290 million in funding would be needed to continue with the project.

Even if that funding was secured, and the final version of its Boeing 2707 was cleared to fly, it was unlikely that Qantas would be able to take delivery of its first Boeing supersonic jet until at least 1979.

The Boeing SST’s European rival, Concorde, had already taken its first flight in 1969 (equipped with windows, contrary to Qantas' initial expectations), putting Boeing further behind.

In 1971, the US Government denied Boeing the funding it needed to continue with its supersonic plans, and the SST program was ultimately scrapped – leaving the Concorde as Qantas’ only hope of supersonic flight.

Bill Abbott

Concorde’s manufacturers move towards a hard sell

With the Boeing SST out of the contest, and keen for Qantas to turn its Concorde options into firm orders, the aircraft’s manufacturer left no stone unturned in persuading the Red Roo to hop onboard.

Its pitches from January 1972 included everything from a new corporate slogan that Qantas could adopt – “The world’s supersonic round-the-world airline” – through to fare pricing guidelines, and even suggestions as to how the Concorde could complement the Boeing 747s, in which Qantas had already made a hefty investment.

If Qantas decided to retain first class on its Boeing 747s after introducing the Concorde to its fleet, it was proposed that fares aboard the Concorde would need to be priced at least 10% higher than the day’s Boeing 747 first class tickets: otherwise, nobody would choose the slower Boeing 747.

Alternatively, Concorde could become an all-first-class plane in the Qantas fleet, with its Boeing 747s instead being fitted exclusively with economy class seating from tip to tail. Passengers would then book their journey not specifically by cabin class, but by speed.

As The Sydney Morning Herald’s Transport Correspondent Gordon Stepto observed at the time, “the important minority for whom time means more than money will fly by Concorde, and the majority for whom money means more than time will fly by subsonic jet.”

But within just a few short months, Qantas’ enthusiasm for supersonic travel had waned substantially. Concorde may have been twice as fast, but the economics of a plane more than twice its size became impossible to ignore.

Qantas turns its back on the Concorde

Between April and June 1972, senior Qantas staffers began playing down the possibility of the Concorde ever flying for Qantas.

“The time is not generally favourable for another aircraft type,” observed J. M. Stinson, an economics officer for research and development at Qantas. “Many airlines would like to see the supersonic era deferred.”

Taking an environmental view, Qantas Senior Captain Alan Terrell added that even if Qantas did buy the Concorde, flights wouldn’t go above 59,000 feet until the impact on the earth’s ozone layer was better known.

“Qantas is not going to inflict anything on the community which the community does not want,” Terrell added.

But the clearest rejection of all came from then-Qantas CEO Bert Ritchie, after taking a tour of the Concorde as it visited Sydney.

When The Australian asked if Qantas would be ordering the Concorde, Ritchie replied, “not unless you fancy flying to Europe in something the size of a London Tube train carriage.”

Even if opinion at Qantas turned in favour of the Concorde, at this stage, its manufacturer reportedly still hadn’t supplied Qantas with a final price for the aircraft, or a performance guarantee: both of which would be necessary for any firm purchase decision to be made.

With Qantas still owned by the federal government in 1973, Australia’s Minister for Civil Aviation, Charles Jones, oddly wasn’t concerned about the ‘sonic boom’ which the jet made at supersonic speeds.

Instead, the noise made by a Qantas Concorde when departing from and arriving into Australian airports – nearby which, many people lived and worked – was seen as far more impactful.

“The more I look at it, the more certain I am that the major problem will be airport noise rather than sonic boom,” Jones said. “I think (Concorde) still has to go some way before it accords with Australian standards.”

Final call: Concorde about to depart

That same month, both Pan American (Pan Am) and Trans World Airlines (TWA) axed their plans to buy the Concorde, cancelling the options they’d placed on the jets – a move that was quickly followed by American Airlines and Continental Airlines the next month.

Eduard Marmet

Not wanting Qantas to join the cancellation list, British Aircraft Corporation, one of the companies behind Concorde, doubled down on its efforts to get Qantas to buy: even flagging that ‘options’ to buy the Concorde would be withdrawn.

“At the time the options idea was started in the middle of the 1960s, Concorde’s planners were looking a very long way ahead,” said a BAC spokesperson. “Since then, the situation has changed considerably.”

Qantas didn’t budge, citing concerns that the jet would be unable to fly from Sydney to Singapore at full payload without making a fuel stop, and in June 1973, the airline got its deposits back on the four Concordes it had originally eyed.

At the time, a Qantas spokesperson indicated that discussions with the Concorde’s manufacturers were ongoing, and that “as far as Qantas is concerned, the issue is not closed,” leaving the door open to a new deal if the numbers finally stacked up.

The Boeing 747 steps up and soars ahead

Concorde’s major advantage was, of course, its speed: and even though rival subsonic jets could never match that, they were busy making their own improvements, like being able to fly further on a single tank of fuel.

That’s exactly what Qantas was promised with the improved Boeing 747-300, placing Sydney and London just one stop apart: shaving not only an entire stopover (previously, there were two), but also four hours from existing flight times between the cities.

Qantas didn’t hesitate to order the Boeing 747-300, which would trim its flight times between Sydney and London down to 22 hours: only 6.5 hours longer than the same journey was projected to take on the Concorde.

By this stage, most of the demand on the Kangaroo Route was in economy class – which Qantas’ original jumbo jets had helped to stimulate, and which the Concorde would lack – making the prospects of Concorde ever flying for Qantas even less likely.

Read more: The Qantas Boeing 747: looking back on a half-century of flying

Scheduling seals the Concorde’s fate

When compared side-by-side with subsonic planes like the Boeing 747, there’s no denying that Concorde would have flown passengers to their destination faster than its rivals: but that comparison only stands true when the number of Concorde flights meets, or exceeds, those offered by other jets.

With a potential order of just four Concordes and a number of routes to fly them on, Qantas expected it would only be able to fly Concorde from Australia to Europe three times per week.

Yet, at the same time, both Qantas and British Airways were already running Boeing 747 flights between Australia and Europe at least daily, if not more regularly.

Concorde may be 6.5 hours faster in the sky, but if passengers had to wait two or even three days to catch the next Concorde flight to their destination, they’d have saved more time by taking an earlier, albeit slower, Boeing 747 service.

Time, after all, was Concorde’s key selling point – and if any hope remained for Qantas and the Concorde, the introduction of the Boeing 747SP into the Qantas fleet would finally close the Concorde chapter in the airline’s history books, with the jumbo emerging not only as the Queen of the Skies, but also the crown jewel of Qantas' fleet.

Also read: A supersonic blast from the past – we visit the record-setting British Airways Concorde